So from a peak of inflated expectations we should not be surprised to see RPA now entering a trough of disillusionment, with surveys showing significant levels of user dissatisfaction. Phil Fersht of HfS explains this in terms that will largely be familiar from previous technological innovations.

- The over-hyping of how "easy" this is

- Lack of real experiences being shared publicly

- Huge translation issues between business and IT

- Obsession with "numbers of bots deployed" versus quality of outcomes

- Failure of the "Big iron" ERP vendors and the digital juggernauts to embrace RPA

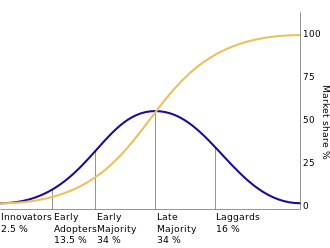

There are some generic models and patterns of technology adoption and diffusion that are largely independent of the specific technology in question. When Everett Rogers and his colleagues did the original research on the adoption of new technology by farmers in the 1950s, it made sense to identify a spectrum of attitudes, with "innovators" and "early adopters" at one end, and with "late adopters" or "laggards" at the other end. Clearly some people can be attracted by a plausible story of future potential, while others need to see convincing evidence that an innovation has already succeeded elsewhere.

|

| Diffusion of Innovations (Source: Wikipedia) |

Obviously adoption by organizations is a slightly more complicated matter than adoption by individual farmers, but we can find a similar spread of attitudes within a single large organization. There may be some limited funding to carry out early trials of selected technologies (what Fersht describes as "sometimes painful experimentation"), but in the absence of positive results it gets progressively harder to justify continued funding. Opposition from elsewhere in the organization comes not only from people who are generally sceptical about technology adoption, but also from people who wish to direct the available resources towards some even newer and sexier technology. The "pioneers" have moved on to something else, and the "settlers" aren't yet ready to settle. There is a discontinuity in the adoption curve, which Geoffrey Moore calls "crossing the chasm".

Note: The terms "pioneers" and "settlers" refers to the trimodal approach. See my post Beyond Bimodal (May 2016).

But as Fersht indicates, there are some specific challenges for RPA in particular. Although it's supposed to be about process automation, some of the use cases I've seen are simply doing localized application patching, using robots to perform adhoc swivel-chair integration. Not even paving the cow-paths, but paving the workarounds. Tool vendors such as KOFAX recommend specific robotic types for different patching requirements. The problem with this patchwork approach to automation is that while each patch may make sense in isolation, the overall architecture progressively becomes more complicated.

There is a common view of process optimization that suggests you concentrate on fixing the bottlenecks, as if the rest of the process can look after itself, and this view has been adopted by many people in the RPA world. For example Ayshwarya Venkataraman, who describes herself on Linked-In as a technology evangelist, asserts that "process optimization can be easily achieved by automating some tasks in a process".

But fixing a bottleneck in one place often exposes a bottleneck somewhere else. Moreover, complicated workflow solutions may be subject to Braess's paradox, which says that under certain circumstances adding capacity to a network can actually slow it down. So you really need to understand the whole end-to-end process (or system-of-systems).

And there's an ethical point here as well. Human-computer processes need to be designed not only for efficiency and reliability but also for job satisfaction. The robots should be configured to serve the people, not just taking over the easily-automated tasks and leaving the human with a fragmented and incoherent job serving the robots.

And the more bots you've got (the more bot licences you've bought), the challenge shifts from getting each bot to work properly to combining large numbers of bots in a meaningful and coordinated way. Adding a single robotic patch to an existing process may deliver short-term benefits, but how are users supposed to mobilize and combine hundreds of bots in a coherent and flexible manner, to deliver real lasting enterprise-scale value? Ravi Ramamurthy believes that a rich ecosystem of interoperable robots will enable a proliferation of automation - but we aren't quite there yet.

Phil Fersht, Gartner: 96% of customers are getting real value from RPA? Really? (HfS 23 May 2017), With 44% dissatisfaction, it's time to get real about the struggles of RPA 1.0 (HfS, 31 July 2019)

Geoffrey Moore, Crossing the Chasm (1991)

Susan Moore, Gartner Says Worldwide Robotic Process Automation Software Market Grew 63% in 2018 (Gartner, 24 June 2019)

Ravi Ramamurthy, Is Robotic Automation just a patchwork? (6 December 2015)

Everett Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations (First published 1962, 5th edition 2003)

Daniel Schmidt, 4 Indispensable Types of Robots (and How to Use Them) (KOFAX Blog, 10 April 2018)

Alex Seran, More than Hype: Real Value of Robotic Process Automation (RPA) (Huron, October 2018)

Sony Shetty, Gartner Says Worldwide Spending on Robotic Process Automation Software to Reach $680 Million in 2018 (Gartner, 13 November 2018)

Ayshwarya Venkataraman, How Robotic Process Automation Renounces Swivel Chair Automation with a Digital Workforce (Aspire Systems, 5 June 2018)

Wikipedia: Braess's Paradox, Diffusion of Innovations, Technology Adoption Lifecycle

Related posts: Process Automation and Intelligence (August 2019), Automation Ethics (August 2019)