Wednesday, June 26, 2019

Listening for Trouble

ProPublica recently tested one such system, enrolling some students to produce a range of sounds that might or might not trigger the alarm. They also talked to some of the organizations using it, including a hospital in New Jersey that has now decommissioned the system, following a trial that (among other things) failed to detect a seriously agitated patient. ProPublica's conclusion was that the system was "less than reliable".

Sound Intelligence is a Dutch company, which has been fitting microphones into street cameras for over ten years, in the Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe. This was approved by the Dutch Data Protection Regulator on the argument that the cameras are only switched on after someone screams, so the privacy risk is reduced.

But Dutch cities can be pretty quiet. As one of the developers admitted to the New Yorker in 2008, "We don’t have enough aggression to train the system properly". Many experts have questioned the validity of installing the system in an entirely different environment, and Sound Intelligence refused to reveal the source of the training data, including whether the data had been collected in schools.

In theory, a genuine scream can be identified by a sound pattern that indicates a partial loss of control of the vocal chords, although the accurate detection of this difference can be compromised by audio distortion (known as clipping). When people scream on demand, they protect their vocal chords and do not produce the same sound. (Actors are taught to simulate screams, but the technology can supposedly tell the difference.) So it probably matters whether the system is trained and tested using real screams or fake ones. (Of course, one might have difficulty persuading an ethics committee to approve the systematic production and collection of real screams.)

Can any harm can be caused by such technologies? Apart from the fact that schools may be wasting money on stuff that doesn't actually work, there is a fairly diffuse harm of unnecessary surveillance. Students may learn to suppress all varieties of loud noises, including sounds of celebration and joy. There may also be opportunities for the technologies to be used as a tool for harming someone - for example, by playing a doctored version of a student's voice in order to get that student into trouble. Or if the security guard is a bit trigger-happy, killed.

Technologies like this can often be gamed. For example, a student or ex-student planning an act of violence would be aware of the system and would have had ample opportunity to test what sounds it did or didn't respond to.

Obviously no technology is completely risk-free. If a technology provides genuine benefits in terms of protecting people from real threats, then this may outweigh any negative side-effects. But if the benefits are unproven or imaginary, as ProPublica suggests, this is a more difficult equation.

ProPublica quoted a school principal from a quiet leafy suburb, who justified the system as providing "a bit of extra peace of mind". This could be interpreted as a desire to reassure parents with a false sense of security. Which might be justifiable if it allowed children and teachers to concentrate on schoolwork rather than worrying unnecessarily about unlikely scenarios, or pushing for more extreme measures such as arming the teachers. (But there is always an ethical question mark over security theatre of this kind.)

But let's go back to the nightmare scenario that the system is supposed to protect against. If a school or hospital equipped with this system were to experience a mass shooting incident, and the system failed to detect the incident quickly enough (which on the ProPublica evidence seems quite likely), the incident investigators might want to look at sound recordings from the system. Fortunately, these microphones "allow administrators to record, replay and store those snippets of conversation indefinitely". So that's alright then.

In addition to publishing its findings, ProPublica also published the methodology used for testing and analysis. The first point to note is that this was done with the active collaboration from the supplier. It seems they were provided with good technical information, including the internal architecture of the device and the exact specification of the microphone used. They were able to obtain an exactly equivalent microphone, and could rewire the device and intercept the signals. They discarded samples that had been subject to clipping.

The effectiveness of any independent testing and evaluation is clearly affected by the degree of transparency of the solution, and the degree of cooperation and support provided by the supplier and the users. So this case study has implications, not only for the testing of devices, but also for transparency and system access.

Jack Gillum and Jeff Kao, Aggression Detectors: The Unproven, Invasive Surveillance Technology Schools Are Using to Monitor Students (ProPublica, 25 June 2019)

Jeff Kao and Jack Gillum, Methodology: How We Tested an Aggression Detection Algorithm (ProPublica, 25 June 2019)

John Seabrook, Hello, Hal (New Yorker, 16 June 2008)

P.W.J. van Hengel and T.C. Andringa, Verbal aggression detection in complex social environments (IEEE Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance, 2007)

Groningen makes “listening cameras" permanent (Statewatch, Vol 16 no 5/6, August-December 2006)

Wikipedia: Clipping (Audio)

Related posts: Affective Computing (March 2019), False Sense of Security (June 2019)

Updated 28 June 2019. Thanks to Peter Sandman for pointing out a lack of clarity in the previous version.

Thursday, March 07, 2019

Affective Computing

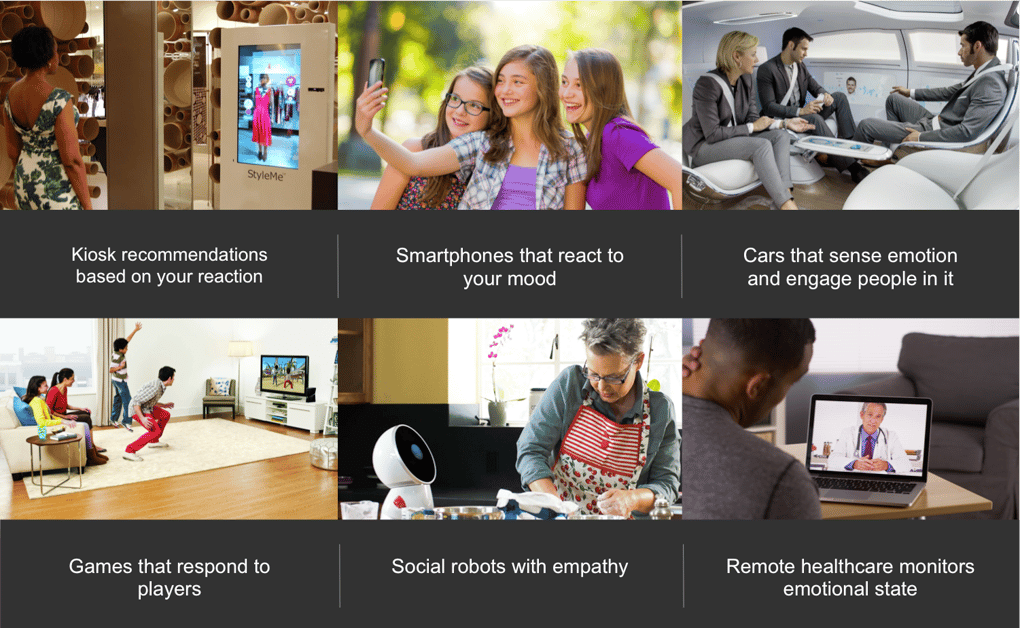

What if doctors could objectively measure your mental state?Dr el-Kaliouby is one of the pioneers of affective computing, and is founder of a company called Affectiva. Some of her early work was building apps that helped autistic people to read expressions. She now argues that

artificial emotional intelligence is key to building reciprocal trust between humans and AI.

Affectiva competes with some of the big tech companies (including Amazon, IBM and Microsoft), which now offer

emotional analysisor

sentiment analysisalongside facial recognition.

One proposed use of this technology is in the classroom. The idea is to install a webcam in the classroom: the system watches the students, monitors their emotional state, and gives feedback to the teacher in order to maximize student engagement. (For example, Mark Lieberman reports a university trial in Minnesota, based on the Microsoft system. Lieberman includes some sceptical voices in his report, and the trial is discussed further in the 2018 AI Now report.)

So how do such systems work? The computer is trained to recognize a

happyface by being shown large numbers of images of happy faces. This depends on a team of human coders labelling the images.

And this coding generally relies on a

classicaltheory of emotions. Much of this work is credited to a research psychologist called Paul Ekman, who developed a Facial Action Coding System (FACS). Most of these programs use a version called EMFACS, which detects six or seven supposedly universal emotions: anger, contempt, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness and surprise. The idea is that because these emotions are

hardwired, they can be detected by observing facial muscle movements.

Lisa Feldman Barrett, one of the leading critics of the classical theory, argues that emotions are more complicated, and are a product of one's upbringing and environment.

Emotions are real, but not in the objective sense that molecules or neurons are real. They are real in the same sense that money is real – that is, hardly an illusion, but a product of human agreement.

It has also been observed that people from different parts of the world, or from different ethnic groups, express emotions differently. (Who knew?) Algorithms that fail to deal with ethnic diversity may be grossly inaccurate and set people up for racial discrimination. For example, in a recent study of two facial recognition software products, one product consistently interpreted black sportsmen as angrier than white sportsmen, while the other labelled the black subjects as contemptuous.

But Affectiva prides itself on dealing with ethnic diversity. When Rana el-Kaliouby spoke to Oscar Schwartz recently, while acknowledging that the technology is not foolproof, she insisted on the importance of collecting

diverse data setsin order to compile

ethnically based benchmarks ... codified assumptions about how an emotion is expressed within different ethnic cultures. In her most recent video, she also insisted on the importance of diversity of the team building these systems.

Shoshana Zuboff describes sentiment analysis as yet another example of the behavioural surplus that helps Big Tech accumulate what she calls surveillance capital.

Zuboff relies heavily on a long interview with el-Kaliouby in the New Yorker in 2015, where she expressed optimism about the potential of this technology, not only to read emotions but to affect them.Your unconscious - where feelings form before there are words to express them - must be recast as simply one more sources of raw-material supply for machine rendition and analysis, all of it for the sake of more-perfect prediction. ... This complex of machine intelligence is trained to isolate, capture, and render the most subtle and intimate behaviors, from an inadvertent blink to a jaw that slackens in surprise for a fraction of a second.Zuboff 2019, pp 282-3

In her talk last month, without explicitly mentioning Zuboff's book, el-Kaliouby put a strong emphasis on the ethical values of Affectiva, explaining that they have turned down offers of funding from security, surveillance and lie detection, to concentrate on such areas as safety and mental health. I wonder if IBM ("Principles for the Cognitive Era") and Microsoft ("The Future Computed: Artificial Intelligence and its Role in Society") will take the same position?I do believe that if we have information about your emotional experiences we can help you be in a more positive mood and influence your wellness.

HT @scarschwartz @raffiwriter

AI Now Report 2018 (AI Now Institute, December 2018)

Bernd Bösel and Serjoscha Wiemer (eds), Affective Transformations: Politics—Algorithms—Media (Meson Press, 2020)

Hannah Devlin, AI systems claiming to 'read' emotions pose discrimination risks (Guardian,16 February 2020)

Rana el-Kaliouby, Teaching Machines to Feel (Bloomberg via YouTube, 20 Sep 2017), Emotional Intelligence (New York Times via YouTube, 6 Mar 2019)

Lisa Feldman Barrett, Psychological Construction: The Darwinian Approach to the Science of Emotion (Emotion Review Vol. 5, No. 4, October 2013) pp 379 –389

Douglas Heaven, Why faces don't always tell the truth about feelings (Nature, 26 February 2020)

Raffi Khatchadourian, We Know How You Feel (New Yorker, 19 January 2015)

Mark Lieberman, Sentiment Analysis Allows Instructors to Shape Course Content around Students’ Emotions, Inside Higher Education , February 20, 2018,

Lauren Rhue, Racial Influence on Automated Perceptions of Emotions (November 9, 2018) http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3281765

Oscar Schwartz, Don’t look now: why you should be worried about machines reading your emotions (The Guardian, 6 Mar 2019)

Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (UK Edition: Profile Books, 2019)

Wikipedia: Facial Action Coding System

Related posts: Linking Facial Expressions (September 2009), Data and Intelligence Principles from Major Players (June 2018), Shoshana Zuboff on Surveillance Capitalism (February 2019), Listening for Trouble (June 2019)

Links added February 2020

Sunday, February 24, 2019

Hidden Functionality

So what's new? A few years ago, people were getting worried about a microphone inside the Samsung Smart TV that would eavesdrop your conversations. (HT @Parker Higgins)

But at least in those cases we think we know which corporation is responsible. In other cases, this may not be so clear-cut. For example, who decided to install a camera into the seat-back entertainment systems used by several airlines?

And there is a much more general problem here. It is usually cheaper to use general-purpose hardware than to design special purpose hardware. For this reason, most IoT devices have far more processing power and functionality than they strictly need. This extra functionality carries two dangers. Firstly,

So who is responsible for the failure of a component to act properly, who is responsible for the limitation of purpose, and how can this responsibility be transparently enforced?

Some US politicians have started talking about a technology version of "food labelling" - so that people can avoid products and services if they are sensitive to a particular "ingredient". With physical products, this information would presumably be added to the safety leaflet that you find in the box whenever you buy anything electrical. With online services, this information should be included in the Privacy Notice, which again nobody reads. (There are various estimates about the number of weeks it would take you to read all these notices.) So clearly it is unreasonable to expect the consumer to police this kind of thing.

Just as the supermarkets have a "free from" aisle where they sell all the overpriced gluten-free food, perhaps we can ask electronics retailers to have a "connectivity-free" section, where the products can be guaranteed safe from Ray Ozzie's latest initiative, which is to build devices that connect automatically by default, rather than wait for the user to switch the connectivity on. (Hasn't he heard of privacy and security by default?)

And of course high-tech functionality is no longer limited to products that are obviously electrical. The RFID tags in your clothes may not always be deactivated when you leave the store. And for other examples of SmartClothing, check out my posts on Wearable Tech.

Nick Bastone, Google says the built-in microphone it never told Nest users about was 'never supposed to be a secret' (Business Insider, 19 February 2019)

Nick Bastone, Democratic presidential candidates are tearing into Google for the hidden Nest microphone, and calling for tech gadget 'ingredients' labels (Business Insider, 21 February 2019)

Ina Fried, Exclusive: Ray Ozzie wants to wirelessly connect the world (Axios, 22 February 2019)

Melissa Locker, Someone found cameras in Singapore Airlines’ in-flight entertainment system (Fast Company, 20 February 2019)

Ben Schoon, Nest Secure can now be turned into another Google Assistant speaker for your home (9 to 5 Google, 4 February 2019)

Related posts: Have you got Big Data in your Underwear? (December 2014), Towards the Internet of Underthings (November 2015), Pax Technica - On Risk and Security (November 2017), Outdated Assumptions - Connectivity Hunger (June 2018), Shoshana Zuboff on Surveillance Capitalism (February 2019)

Sunday, December 03, 2017

IOT is coming to town

You better watch out

#WatchOut Analysis of smartwatches for children (Norwegian Consumer Council, October 2017). BoingBoing comments that

Kids' smart watches are a security/privacy dumpster-fire.

Charlie Osborne, Smartwatch security fails to impress: Top devices vulnerable to cyberattack (ZDNet, 22 July 2015)

A new study into the security of smartwatches found that 100 percent of popular device models contain severe vulnerabilities.

Matt Hamblen, As smartwatches gain traction, personal data privacy worries mount (Computerworld, 22 May 2015)

Companies could use wearables to track employees' fitness, or even their whereabouts.

You better not cry

|

| Source: Affectiva |

Six Wearables to Track Your Emotions (A Plan For Living)

Soon it might be just as common to track your emotions with a wearable device as it is to monitor your physical health.

Anna Umanenko, Emotion-sensing technology in the Internet of Things (Onyx Systems)

Better not pout

Mingzhe Jiang et al, IoT-based Remote Facial Expression Monitoring System with sEMG Signal (IEEE 2016)

Facial expression recognition is studied across several fields such as human emotional intelligence in human-computer interaction to help improving machine intelligence, patient monitoring and diagnosis in clinical treatment.

I'm telling you why

Maria Korolov, Report: Surveillance cameras most dangerous IoT devices in enterprise (CSO, 17 November 2016)

Networked security cameras are the most likely to have vulnerabilities.

Leor Grebler, Why do IOT devices die (Medium, 3 December 2017)

IOT is coming to town

It's making a list And checking it twice

Daan Pepijn, Is blockchain tech the missing link for the success of IoT? (TNW, 21 September 2017)

Gonna find out Who's naughty and nice

Police Using IoT To Detect Crime (Cyber Security Intelligence, 14 Feb 2017)

James Pallister, Will the Internet of Things set family life back 100 years? (Design Council, 3 September 2015)

It sees you when you're sleeping It knows when you're awake

But don't just monitor your sleep. Understand it. The Sense app gives you instant access to everything you could want to know about your sleep. View a detailed breakdown of your sleep cycles, see what happened during your night, discover trends in your sleep quality, and more. (Hello)

Octav G, Samsung’s SLEEPsense is an IoT-enabled sleep tracker (SAM Mobile, 2 September 2015)

It knows if you've been bad or good So be good for goodness sake!

Ben Rossi, IoT and free will: how artificial intelligence will trigger a new nanny state (Information Age, 7 June 2016)

Twitter Version

Thread on #Privacy and the #InternetOfThings— Richard Veryard (@richardveryard) December 4, 2017

Related Posts

Pax Technica - The Book (November 2017)

Pax Technica - The Conference (November 2017)

Pax Technica - On Risk and Security (November 2017)

The Smell of Data (December 2017)

Updated 10 December 2017